Maximizing Designer Effectiveness in a Convergent World

Keith Williams, MBA

Purdue University

Pao Hall of Performing Arts

552 West Wood Street

West Lafayette, Indiana, USA 47907

Abstract

Designers practice at the convergence of multiple disciplines: technology/engineering, art/aesthetics, manufacturing, business/strategy, and sociology/consumer behavior. How does a designer navigate within so many disparate areas? What attributes separates a design that is held in the highest esteem with one that never achieves significant success or recognition? This paper looks at three key areas: Designer-Creator, Designer-Strategist, and Designer-Visionary. Attributes of each area are discussed and interplay between them yields a method of defining a design and applicable method of operation to maximize the designer’s effectiveness.

Keywords-industrial design, return-on-investment, strategy, cross-discipline, market awareness, customer value, business strategy, innovation, brand awareness, visionary, maker, leadership

Methodology

A literature review serves to show the economic benefit, and thus motivation, to invest in industrial design activities within both emerging and mature markets. A breakdown of management and designer needs and expectations are discussed and a rationale for why a symbiotic relationship between the two disciplines needs to exist. The information gathered and analyzed from the literature review justifies the proposed designer framework/model that concludes the paper.

1. Introduction

It has been studied and shown that the involvement of designers by companies can reap significant returns on investment financially as well as from market awareness and customer satisfaction standpoints. The economic benefits serve as the backdrop for corporate motivation to heavily support industrial design efforts within the firm. In short, the financial returns on design serves as a justification for management to champion design efforts.

Despite these benefits, companies have too often either limited designer’s field of influence within the organization to a very narrowly defined skill-set or have broadened their job descriptions to the point that an extreme amount of cross-discipline burden ultimately dilutes the potential impact these individuals can have. This paper attempts to analyze and define a core group of skills that maximize the ability for the designer to create, lead, align with the company’s strategies, and have an overall positive impact for the company.

2. Corporate Management and Designers

2.1 Impact of designer and designers on corporate image and financials

Anecdotally, many companies have had their success stories tied to visionary designers and an active innovation culture. Names such as Apple, Ikea, Starbucks, and Dyson are a small sampling of such well-known brands and companies.

However, managers often struggle with requesting or championing the financial and strategic support necessary for employing highly talented design resources. By their very nature management seeks to minimize the risk of any such outlays and expenditures. They often do this by studying current/past trends and attempt to extrapolate the future based on these data points.1 In addition, financial models and spreadsheets attempt to ward off any potential downsides by rationalizing through numbers. A recent The Economist Intelligence Unit article places the success rate of management-driven strategies 63%, while others argue that number is as low as 10%.2

Designers often operate outside of the comfort zone of management’s premeasured, analytic forecasts. They often employ methods that appear subjective, emotional, experimental, and oscillate between abstract ideas and particular details.1,3 With such a disparity between design and management, why would management ever concede to such a risk and cost?

Studies have shown that companies that rely upon industrial designers have increased brand recognition3,4, higher customer satisfaction1,4, and even improved financial performance5,6 over those companies that do not invest in design. Of particular interest Gesmer and Leendner’s research has been demonstrated that it is best to lead in design innovation than to follow.5,6

It is important to note that the Utterback and Abernathy model of technological evolution5,7 parallels the results of Gesmer and Leendner—the type and financial impact for the company depends upon the maturation of the industry/products and the novelty of design for a given industry.5,7 The Abernathy model states that over time innovation will shift from radical innovations to incremental, cost-cutting advances. However, investment in industrial design was also shown to be important to maintaining financial performance and standing in the marketplace, whether in a mature or emerging market.5

Hertenstein, et al. went deeper with their research seeking to compare return on assets, return on sales, level of sales growth, net income, operating cash flow, and stock market returns between firms with high- and low-levels of industrial design support/activity.5,7 The seven-year aggregate of financial data analyzed showed a consistent correlation of design activity to higher financial performance. In almost all cases the confidence level of the correlation was beyond .01, with two-tail test.7 In other words, there was a greater than 99% confidence that the higher financial returns were impacted by increased industrial design efforts.

2.2 The world of designers

Designers live between doing (designing: verb) and delivering a final product (design: noun).1 Liedtka states that “Real-life behavior, rather than theory, is what matters for design.”1 This underscores the difference, once again, between the pragmatic and number-driven universe of management and the design world, as noted in the last section.

In between the doing and the release of the designed product is a process that is often difficult to objectively measure, as it is a typically non-linear path from project start to end. Designers expect to experiment throughout the process and iterate toward an optimal solution. A key to this process is an extreme bias toward action and doing. Experiential methods allow for the emotional drivers of the project to be lifted up while the pursuit of novelty and the minimization of the status quo underscore the values of the designer. 1,2,8

The designer’s world is built around dealing with uncertainty, as opposed to the analytics of traditional business strategy that excels in mature markets and a more predictable world.1,5 In the end, the products and services that are developed by designers are purchased and consumed by people1,4,8, and the softer, emotional side of meeting human needs carries far more weight than any cold and impersonal business strategy. Designers work within a mastery of observation and iteration to uncover a deep understanding of the motivations and needs that consumers may not be consciously aware of—this is the underpinning of innovation within the realm of product design.1

2.3 Why designers need management

Designers bring a significant value to the product development side of the business and can elevate the company’s performance and perception. However, designers and management must co-exist in a symbiotic environment; each playing to their own strengths and relying on the other to supplement their weaknesses.

Business strategy is the machine that delivers the design to the marketplace. It is also the backbone that captures profits from the consumer to ensure that the company is on solid financial footing and operations can continue unabated. Liedtka defines four major areas that a business strategy or business/product idea must meet in order to be a truly attractive venture: Value Creation, Execution, Scalability, and Defensibility.1 Designers are trained and are well versed in the Value Creation area. However, the other three are within the core-competency of business leaders and management.

Execution, or financial positioning, is a core competency of management and aligning of the design so that the firm may deliver the new product at a price that works for the consumer, but also delivering a profit back to the company is critical for a healthy company.1 Scalability is the business pragmatism regarding the size of the market opportunity for the company and how to seize that opportunity. Beyond simply a size measurement, this attribute takes into consideration time-to-market and the potential impact of the company on the market.1 Defensibility is the understanding of and the ability to maintain a competitive advantage for the company in the marketplace. Having an on-going way to keep other companies from imitating the investment the company has made into the design is one of the key drivers to making sure that the project has a positive return on investment for the company.1,8

3. Designer for the convergent world

3.1 Introduction to designer model

What follows takes the above-mentioned interplay between management and designers and combines those insights with traditional roles that designers play to create a model of designer attributes to be most effective within a convergent world.

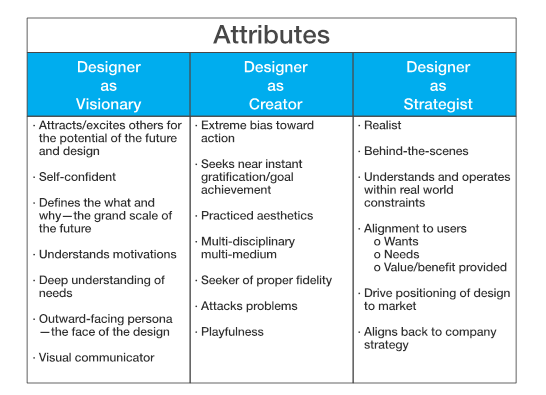

The model presented provides three aspects that define the core competencies for the modern designer. These pillars align with the above-described interactions of designers within the companies whose goals are to drive innovation through design. These characteristics breakdown into the following categories: Designer as Creator, Designer as Visionary, and Designer as Strategist (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

It should be noted that in this model, each of these areas creates a check-and-balance between one another. This allows each area to stretch the others in significant ways, but also to keep one another in alignment with the goals of the company and within a pragmatic worldview of what is possible. The result is affecting a design direction that is appropriate for both the firm as well as the end-user.

![]()

Figure 2 highlights this interplay between the designer personas graphically. The Visionary and Strategist are the main direction drivers, where the Creator can be thought of as providing feedback and data that shades to the Visionary or Strategist side, as appropriate. The macro direction of the design can range from radical to pragmatic as dictated by the Visionary and Strategist struggle for dominance. The left image of Figure 2 shows the Visionary mindset having a much larger influence and pulling the design in a much more innovative direction. The right side of Figure 2 demonstrates the more pragmatic side of the Strategist impacting the design direction.

This model works well with the Utterback and Abernathy product evolution methodology as well as the observations by Gesmer and Leendner showing that the maturation of a product/market has a direct correlation to the financial impact to the company as well as the novelty of the design—incremental designs for mature markets/innovative designs for emerging markets.5,7 In short, a newer product/industry will likely have a much higher innovation level with the Visionary persona having a much larger influence on the design. However, as a product/market matures, incremental improvements in the design and functionality of the product are the rule. As such, the pragmatic Strategist has a much higher impact on the direction of the design.

Table 1.

3.2 Designer as Visionary

A visionary is often held up as the pinnacle of what a great designer should be. The visionary is the designer that has the uncanny ability to see deeply into a scenario, understand the motivations of that consumer, and deliver a simple, yet complete, aesthetically beautiful product that ultimately transcends the ‘thing’ it was designed to be and becomes a timeless icon of an age.

This is an incredible amount of pressure for the visionary to live up to. Indeed, the visionary is often focused not on today, but well into the future that by definition does not yet exist. It is up to the visionary to inspire and communicate the perspective of this future ideal. The visionary also sets the stage for the quality and refinement of the embodiment of the design. Further, it rests on the visionary to align the design with the values and mission of the company and to ensure that the overall team internalizes such values.

The visionary is constantly struggling between the potentials of a perfect tomorrow with a deep understanding of needs and motivations that are the limitations of today. These observations allow the visionary to take on the role of trend forecaster. The visionary operates methodically and with intention. Otherwise, design without vision often leads to mediocrity.

The visionary has a bias to always push toward the perfection that tomorrow promises, only to be held in check by the other two personas of the designer’s triad. The visionary ‘directs’ the maker and informs the strategist and is adept at being a future trend spotter.

3.3 Designer as Creator

The three first characteristics usually attributed to a designer are master of aesthetic application, agile developer/experimenter, and evaluator of results to allow for feedback into the iterative development process. The extreme bias toward action and outcomes manifests itself in physical prototypes or mock-ups that can be quickly tested and evaluated.

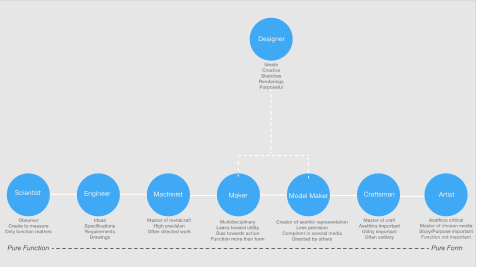

To further clarify the definition of the designer in this role, the following spectrum has been developed that ranges from pure function to pure expression/form (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In order to maintain the velocity required to develop and deploy innovation into the marketplace, it is critical that the experiment/iteration phase move as quickly as possible. One critical way for this to occur is to have the designer be capable of generating a physical embodiment of the current state of the design. Much has been made of the impact of the maker movement has had on the economy, ultimately being dubbed the third industrial revolution.9

The ability to give physical form to the design is integral to gathering feedback and ascertain the kind of understanding that generates innovative outcomes desired by the company, markets, and users. The creator is both pushed by the visionary to perform and create at an extreme level as well as kept within the limits of what is needed and practical by the strategist.

3.4 Designer as Strategist

The strategist is the realist and holds a very pragmatic view of design execution and its alignment with company goals. However, a distinction needs to be made: the Designer as Strategist does not play the corporate management role of strategy. It should be considered that the Designer as Strategist works solidly within the design realm to align the design to the market within real-world constraints and to align the design as closely as possible to corporate strategy.

The strategist keeps the creator and visionary within bounds of the constraints of the project/company goals. In particular, the strategist works to make sure that the visionary brings insight back into focus for the real world and pulls the information gathered from the creator to align the design in such a way to deliver value to the user and the company.

The strategist also strives to properly scope the design to the maturation of the market as well as the expectations of the user and company. This creates the most tension with the visionary, as often the ‘right’ design is not the most ambitious or grandiose. The strategist further refines the direction by looking toward the users with both a design-focused and company-focused lens. This allows the design to properly position the design and as closely align the design sensibilities to the firm’s goals and structure to maximize the potential for success.

4. Conclusion

This paper started by describing the differences between management and design and then made a case for a positive financial impact on the company by an active investment in industrial design. Next, a short deconstruction of who designers and managers are and what motivations they each then led toward a stance of why both camps need to work well together in a symbiotic relationship to maximize their impact for the firm. Finally, the foundation that was laid earlier in the paper is leveraged into a triad of designer personas: Designer as Visionary, Designer as Creator, and Designer as Strategist. These three definitions align with the needs of the firm while maximizing the effect that designers can have both on the firm as well as the users.

References

[1] Liedtka, Jeanne. “Business Strategy and Design: Can This Marriage Be Saved?” Design Management Review, vol. 21, no. 2, 2010, pp. 6–11.

[2] Mankins, Michael, and Richard Steele. “TURNING GREAT STRATEGY INTO GREAT PERFORMANCE.” Harvard Business Review, vol. 83, no. 7,8, 2005, pp. 64–72.

[3] Herm, Steffen, and Jana Möller. “Brand Identification by Product Design: The Impact of Evaluation Mode and Familiarity.” Psychology &Amp; Marketing, vol. 31, no. 12, 2014, pp. 1084–1095.

[4] Freng Svendsen, Mons, et al. “Marketing Strategy and Customer Involvement in Product Development.” European Journal of Marketing, vol. 45, no. 4, 2011, pp. 513–530.

[5] Gemser, Gerda, and Mark A. A. M. Leenders. “How Integrating Industrial Design in the Product Development Process Impacts on Company Performance.” Journal of Product Innovation Management, vol. 18, no. 1, 2001, pp. 28–38.

[6] Hertenstein, Julie H., et al. “The Impact of Industrial Design Effectiveness on Corporate Financial Performance *.” Journal of Product Innovation Management, vol. 22, no. 1, 2005, pp. 3–21.

[7] Utterback, and Abernathy. “A Dynamic Model of Process and Product Innovation.” Omega, vol. 3, no. 6, 1975, pp. 639–656.

[8] Venkatesh, Alladi, et al. “Design Orientation: a Grounded Theory Analysis of Design Thinking and Action.” Marketing Theory, vol. 12, no. 3, 2012, pp. 289–309.

[9] Thilmany, Jean. “The Maker Movement and the U.S. Economy.” Mechanical Engineering-CIME, vol. 136, no. 12, 2014, pp. 28–29.